An open letter to economist Paul Krugman.

Dear Mr. Krugman,

I want to start off by saying that I’ve followed your column in the New York Times over the years, and I have tremendous respect for you. Since I have no background in economics, I appreciate your clear, straightforward approach to breaking down the issues. And more important, I appreciate the fact that you speak out against the dishonesty and fraud that are all too common in this country. There have been times when I really needed to hear the voice of reason, and you have been that voice.

But as much as I respect you, I have to say I think you’re dead wrong about rent control. In fact, I think most economists are wrong about rent control. Not that I have anything in my background to give me any credibility. You went to Yale and MIT. I went to LACC. But in spite of my utter lack of any credentials that would give me the right to talk about this issue, I hope you’ll read on at least a little further. Because when it comes to rent control, I think you, like the vast majority of economists, have failed to do your homework.

Just to give you an idea of the sloppy thinking that characterizes most discussions about rent control, let’s talk about Los Angeles. I live in LA, and I can’t tell you how often I’ve heard that rents are high in LA because of rent control. I’ve been repeatedly told it constrains new construction, which means we have low supply, which means we can’t meet the demand for new housing, and that drives prices up.

But there are a number of problems with this argument.

First, most of the people who talk about LA don’t even understand the difference between the City of Los Angeles and the 87 other cities that make up the County of Los Angeles. Some of these are embedded within the City’s boundaries. While the City of LA does have a Rent Stabilization Ordinance, there are only four other cities (Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, West Hollywood and Thousand Oaks) that have any kind of rent control. Median rents in Culver City, Burbank and Pasadena are as high or higher than the City of Los Angeles, despite the fact that these cities have no rent control ordinance on their books. And within the City of LA you’ll find considerable variation in housing costs. Rents in the corridor between Santa Monica and Downtown tend to be the highest. Rents in parts of the Valley (Arleta, Pacoima, Sylmar) and in the Harbor Area (Wilmington, San Pedro) are usually considerably lower. By itself, this seems to suggest that there are other factors besides rent control which may have a larger impact on rental costs.

Second, those who oppose rent control generally point to coastal cities like LA, San Francisco or New York, all of which have outrageously high housing prices. But absolute dollar amounts aren’t the best gauge of affordability. Really we have to look at prices relative to income, in other words we have to look at rent burden. According to a 2016 report by Abodo , the Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach area was at that time the most cost-burdened rental market in the US. A report from HUD the following year came to the same conclusion. While prices in the Miami area are well below those in New York or San Francisco, wages are also much lower, and renters are getting hammered. This is in spite of the fact that Miami has no rent control. Another report from Abodo that breaks down rent burden by generation finds that a number of urban areas in Florida appear high in the rankings, including Daytona Beach, Lakeland-Winter Haven, Cape Coral-Fort Myers, and Orlando. No Florida cities have enacted rent control, because state law prohibits them from doing so. Supply siders tell us that if landlords are allowed to charge whatever the market will bear, this will incentivize new construction which will generate more supply and bring prices down. That hasn’t happened in Florida. Renters there have been struggling for years, and somehow market forces have failed to bring relief. And while the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim area does appear on Abodo’s 2016 rent burden ranking, it’s interesting to note that it comes in at number five. None of the first four urban areas on the list have rent control. (I should also point out that Long Beach and Anaheim do not have rent control.)

All the economists opposed to rent control insist that endless reams of research back their stance. Again, I’m not an economist, and I certainly haven’t spent as much time with the research as they have, but what I’ve seen doesn’t impress me. For all the talk of irrefutable data, the studies I’ve looked at seem very limited. They generally focus on a narrow selection of markets, sometimes just one market. They often base their conclusions on data that has a questionable relationship to rent control. They generally look at the housing market in isolation, without any effort to see rental prices as part of the larger picture. And they generally don’t acknowledge that there are a lot of different ways you can structure rent control.

No question, the forms of rent control used in the first half of the 20th century were a failure. I agree that setting absolute caps on housing prices stifles new construction and only encourages black market housing arrangements. But the forms of rent control adopted in some cities over the past 50 years are much different from their predecessors. For instance, in LA the Rent Stabilization Ordinance passed in 1978 only applies to apartments built before that year, so it doesn’t discourage new construction. It allows annual rent increases of 3%. Because the ordinance includes vacancy decontrol, rents are reset when a tenant moves out. It also has a mechanism that allows landlords to charge additional amounts to pay for capital improvements and major repairs. I have to laugh when I hear that rent control inevitably leads to poor maintenance of residential units, creating unsightly and unsafe slums. I often pass through Santa Monica, Beverly Hills and West Hollywood, all of which have a form of rent control, and I haven’t noticed any festering swaths of urban decay.

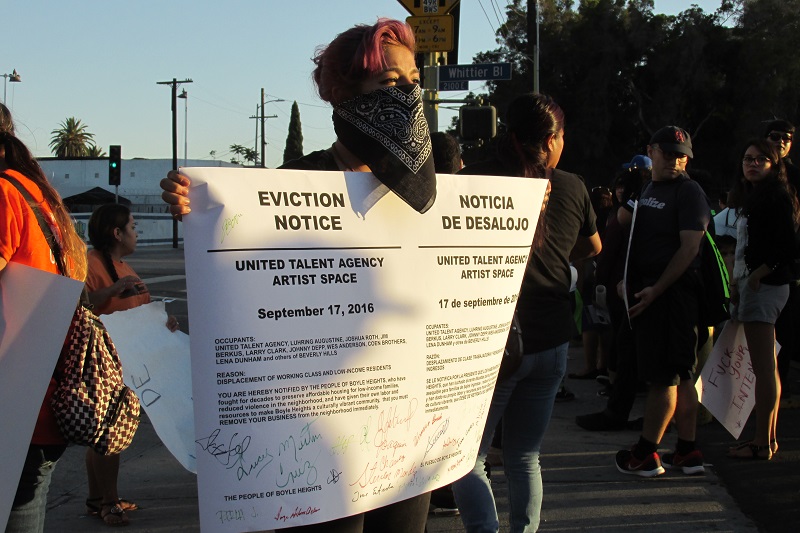

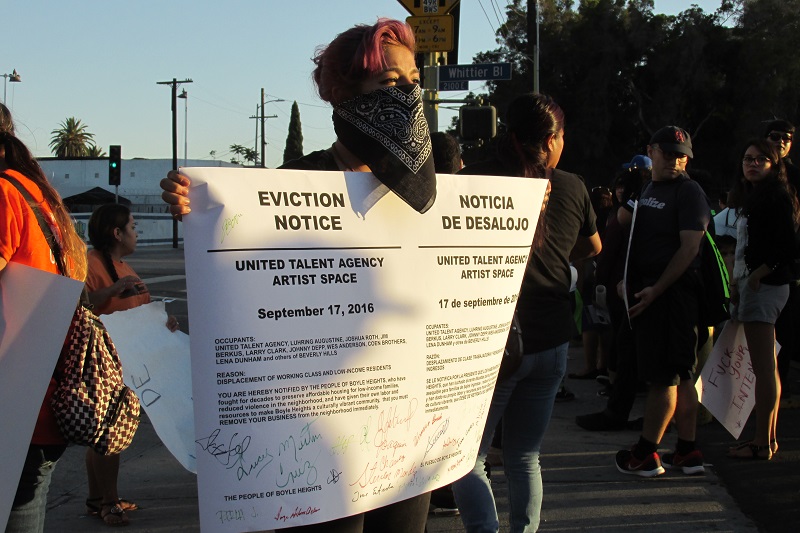

Residents protesting gentrification in East LA.

While I can’t claim to have read every research paper on rent control published in the last 50 years, I have read a sampling, and as I said before, I’m not impressed. To go into specifics, I’d like to talk about a couple of papers that have been widely cited, and then another more recent study….

First let’s take a look at Gyourko and Linneman’s study from 1987, which analyses the allocation of benefits under rent control. They focus on New York City, and they use a lot of impressive formulas to compare the distribution of family income with the distribution of benefit-adjusted income under rent control. I don’t pretend to understand the math. I’ll just assume that all the numbers they come up with are absolutely correct. Their conclusion is that, “[I]f the primary social benefits of rent control are distributional impacts, they were not successful in New York.” They go on to say, “Economists have long predicted that racial discrimination could result in markets where nonprice rationing occurred. Blacks and Puerto Ricans in the controlled sector received lower benefits than their white counterparts.”

I’m sure they’re right when they say that calculating the dollar amounts shows an uneven distribution of monetary benefits. Unfortunately, they’re missing the whole point of rent control. It was never intended to ensure the equal distribution of monetary benefits. The purpose of rent control is to provide housing stability and to minimize the considerable economic and social costs of displacement. It does offer equal protection to all those who live in rent-controlled apartments, regardless of their race, which is why it blows my mind that the authors have the nerve to state, “Economists have long predicted that racial discrimination could result in markets where nonprice rationing occurred.” Are they kidding?! They’re saying rent control results in racial discrimination? Like discrimination never happens when we let the free market rule? This statement is so absurd it really calls the authors’ judgment into question. How clueless do you have to be to blame rent control for a social evil that’s woven into the very fabric of this country?

Another issue that comes up, not just in Gyourko and Linneman’s paper but in others, is the idea of a “rent subsidy”. This is the difference between the rent controlled price for a unit and what someone would pay on the free market. As an example, the authors say “…. if the monthly rent for a controlled apartment was $500 and this unit would have rented over $700 in the uncontrolled sector, the monthly rent control subsidy would be $200.” This is interesting, because it assumes that the free market price is the result of some kind of rational process. But is it?

Let’s look at a recent incident at an apartment complex in City Terrace. The building was sold to Manhattan Manor, a real estate investment group, and because it wasn’t covered by rent control, they decided to jack up the rents. One tenant had their rent go from $1,250 to $2,000 overnight, a 60% increase. Since the building wasn’t covered by rent control, and the tenants couldn’t afford the increase, the new owners started eviction proceedings. But the tenants fought back, and the case went to court. Far from siding with Manhattan Manor, the jury found that the unit had significant habitability issues and that the new owners had failed to make basic repairs. In fact, not only did the jury reject the owners’ bid to evict the tenants, they determined that the unit was only worth $1,050 per month in its current condition.

Now, in Gyourko and Linneman’s view, the new landlords were just exercising their right to reset the rent to what they believed they could get on the free market. And from the economists’ perspective, if the building had been rent controlled, the tenants would have been receiving a “subsidy” of $750 a month. But a jury, after looking at basic habitability issues, decided that the unit wasn’t even worth the $1,250 that the tenants had originally been paying. So the idea that the free market somehow sets fair prices through a rational process seems suspect. And this isn’t an isolated incident. Scenes like this are playing out all over LA, and I suspect, throughout the country. Real estate brokers routinely advertise “underperforming” properties, and in the current environment, with speculation running rampant, investors are happy to snap these buildings up. For many of these investors, the condition of the apartment isn’t a primary consideration in determining what to charge. All they care about is getting the highest possible return on their investment. Unfortunately, in many cases, deciding an apartment’s “fair market value” is just a matter of picking the highest number they think they can get away with.

But let’s move on to Glaeser, Luttmer, 2003. I give them credit. Their paper is one of the few I’ve seen that actually compares cities with rent control to cities without. They look at rental data in New York, Chicago and Hartford, and also create a baseline by taking a sample of Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) across the US. They even break the demographics down by income, household size and education. They’re certainly making an effort to take variables into account. And you could make the argument that the three cities they focus on are similar in a number of ways

Still, there are significant differences that could have an impact on Glaeser and Luttmer’s calculations. To start with, New York is unique. It’s by far the most populous city in the U.S., as well as a financial, educational and cultural center. It’s the point of entry for thousands of immigrants annually and its port is a global shipping hub. The authors use census data from 1990, when New York’s population was 7.322 million, Chicago’s was 2.786 million, and Hartford’s was 137,296. You could still make the case that New York and Chicago are major urban centers and roughly similar when it comes to income and demographics. But the comparison to Hartford, with a population roughly one fiftieth of New York’s, is really questionable.

And while I respect Glaeser and Luttmer for taking the trouble to look at MSAs all over the US to set a baseline, the vast majority of these urban areas have little or nothing in common with New York in terms of population, demographics, employment, income, housing stock, and climate. The idea that we can use the numbers for these areas to set some kind of “normal” to use as a comparison with New York just doesn’t make sense. If your main interest is in working out intricate math problems, the authors’ approach probably sounds great. But if you’re actually looking for answers to complex questions about housing affordability, it just doesn’t make it.

But the biggest problem when it comes to comparisons, even if we’re just talking about New York and Chicago, is density. In New York in 1990 there were 24,165 people per square mile. In Chicago in 1990 there were 11,905 per square mile. In other words, New York is over twice as dense in terms of population as Chicago. Even though the two cities are roughly comparable in terms of housing units per capita, the cost of real estate in New York is way higher, which means the cost of housing is going to be way higher. So while the median income for the two cities is in the same ballpark, you’re going to get less apartment for your buck in New York. Because of this, even if New York didn’t have rent control, you’d expect to see a difference in the kind of housing that New Yorkers could afford compared to the rest of the country.

There are other problems with Glaeser and Luttmer’s paper. On the first page, in talking about mechanisms for rationing goods, they say, “If the allocation mechanisms are not perfectly efficient, then the analysis illustrated by Figure 1, which implicitly assumes that the rationing under rent control ensures that apartments go to the consumers who value them most, is wrong.” The authors seem to be saying that rent control is failure because it’s not “perfectly efficient”. This is an interesting way to define failure when it comes to the housing market. Is the free market “perfectly efficient” when it comes to allocating housing resources? Of course not. When it comes to housing, perfect efficiency is nothing more than an abstract concept. Glaeser and Luttmer base their argument on their own false assumption. They make a claim for rent control that its supporters never have. I’ve never heard anyone claim that rent control is perfectly efficient. Let me repeat, the point of rent control is to provide stable housing and to prevent displacement.

But let’s get to the crux of Glaeser and Luttmer’s argument. For these two academics, the efficient allocation of assets is their Holy Grail. How do they define that in the housing market? “The baseline apartment characteristic used to estimate misallocation is the number of rooms in the apartment.” Huh. Interesting. So they look at the data for New York, Chicago and Hartford, and what do they find? “Our methodology suggests that 21 percent of New York apartment renters live in apartments with more or fewer rooms than they would if they were living in a free-market city.”

Really? That’s the criterion they use? Whether New Yorkers are living in “apartments with more or fewer rooms than they would if they were living in a free-market city.” Honestly, this seems pretty arbitrary. If the outcome was that a lot of New Yorkers were living in apartments with too few rooms, that would fit in with the standard argument that rent control decreases supply. But in their minds, having too many rooms is just as bad as having too few rooms. They say that, according to their calculations, “…the overall percentage of New York renters that are living in apartments that are the wrong size is 25.8%….” And what’s the right size? It’s a ratio they came up with by crunching data for a selection of U.S. cities, most of which are completely different from New York when it comes to employment, income, housing stock, and demographics.

Glaeser and Luttmer seem to believe there’s some kind of ideal that will result from the “perfect allocation” of housing resources, and that the free market will achieve that ideal. But even though all of us want to live in a place where there’s enough room to be comfortable, the key issue for renters is affordability. While Glaeser and Luttmer worry about the right number of rooms, you can see increasing numbers of tenants worried about just making rent in cities like Miami, Portland, and Austin, none of which have rent control. And the free market doesn’t seem to have helped tenants in Clark County, Nevada, where official data says that there were 30,000 evictions in 2016 alone. Interestingly, most housing experts in the area agree that the actual number is much higher, since many tenants who fall behind on rent just leave to avoid having an eviction on their record.

Ultimately, I have to say that Glaeser and Luttmer’s work isn’t very convincing. I give them credit for crunching a lot of numbers, but their conclusions seem pretty arbitrary. Like many economists who tackle rent control, they’re more focussed on the numbers than they are on reality. Rather than looking at the pressures the economy brings to bear on renters, rather than examining the impacts of speculative real estate investment, rather than measuring the social impacts of displacement, they spend their time counting the number of rooms a household has. And because in New York they find that those numbers don’t add up according to an an ideal ratio they’ve decided on, their verdict is that rent control is a failure.

Downtown LA now offers “boutique apartment lofts”.

The most recent study I looked at was the 2017 paper from Diamond, McQuade and Qian, a trio of academics at Stanford. Their work was just as disappointing as the others. Like Gyourko and Linneman, these folks have decided they can analyze the impacts of rent control by looking at a single city. They feel perfectly comfortable making sweeping statements about the negative effects of rent control without considering what tenants are dealing with in other cities governed by the free market.

The folks from Stanford study decades of data from San Francisco and find that rent-controlled units are more likely to be removed from the market through legal conversions than units not covered by rent control. They argue that because of these conversions the supply of rental units shrinks and therefore rental prices rise. “We conclude that this led to a city-wide rent increase of 7% and caused $5 billion of welfare losses to all renters.” Well, that may sound logical on the face of it, but without comparing their data with rent increases in free market cities, it’s pretty meaningless. To claim any certainty about the actual rate of rent increases due to conversions you’d need to do more than study a single city. You’d have to compare your results to other cities without rent control to see if rents rose even without such conversions. Like, maybe Orlando, where Apartment List reports that rents rose 5.3% from August 2017 to August 2018. Or how about Denver, where a June 2018 report from Zumper says that in a single year the rent for a one-bedroom rose 16%.

This isn’t the only questionable conclusion that the folks from Stanford come to. Check this out….

“Taken together, we see rent controlled [sic?] increased property investment, demolition and reconstruction of new buildings, conversion to owner occupied housing and a decline of the number of renters per building. All of these responses lead to a housing stock which caters to higher income individuals. Rent control has actually fueled the gentrification of San Francisco, the exact opposite of the policy’s intended goal.”

This is fascinating. Because the authors see an increase in high-cost housing, they come to the conclusion that rent control accelerates gentrification. But this is based on the assumption that San Francisco housing prices only increased due to conversions, which is ridiculous. The fact is, real estate investors looking for the highest rate of return will do whatever’s required to squeeze more money out of a building. Sure, in San Francisco they resort to conversions to free themselves from rent control. But in markets without rent control they’d just jack up the rent as high as they pleased, and the end result would would still be the displacement of low-income residents by high-income residents. Free market cities like Portland, Austin and Denver have gentrified rapidly over the past 15 years.

Seriously, the authors are totally clueless on this point. They’re so busy fondling their data that they completely ignore the reality of what’s been happening in San Francisco. As the Bay Area has become a tech hub, wave after wave of high-paid employees have flocked to the city. Seeing this, real estate investors have bought up all the units they can in order to capture some of that cash. Even if San Francisco had never enacted any kind of rent control, prices would still be rising like crazy. Low- and middle-income tenants would still be getting hit with exorbitant rent increases as housing speculators swarmed over the city to cash in on the tech boom. These conversions aren’t the cause of higher prices, they’re just a tool. Given the rise of the tech sector in San Francisco and the flow of global real estate investment into the city, prices would be shooting up with or without rent control, and the end result would still be massive displacement of low-income residents.

Mr. Krugman, you seem pretty cool, so I hate to make sweeping generalizations about economists. But after looking at these three papers, and others on rent control, I have to say their authors all have one thing in common. They’re so focussed on crunching numbers they seem completely out of touch with reality. These academics have certainly spent a lot of time compiling data and working out complex equations, but did they even spend five minutes talking to renters in the cities they were studying? They analyze rental markets in terms of dollar amounts and the number of rooms, but did they spend any time looking at how renters are struggling in the current housing market? Did they even consider looking at displacement in free market cities like Miami, Portland and Austin? Did they ever consider that speculative investment could cause rapid distortions in the housing market that would leave renters out in the cold?

No. They look at isolated datasets and after adding up the numbers they come to the conclusion that rent control is incontestably bad. But their work is narrow and shallow. Of the three studies cited here, only one of them actually compares rent controlled cities to free market cities. And in that case the authors state that rent control should be perfectly efficient, without ever asking if the free market is perfectly efficient when it comes to housing. They claim that rent control distorts the housing market without considering whether other factors could distort the market as well.

But I want to be clear. I’m not saying you should come out in favor of rent control. I’m saying that, based on the research I’ve looked at, no economist should come out against it. It’s entirely possible that there are other, better papers I missed, and if that’s the case, you can dismiss me as an ignorant fool. But the studies by Gyourko, Linneman and Glaeser, Luttmer have been widely cited, which seems to indicate that economists give them credence. Honestly, I can’t understand why. While I’m sure these academics worked hard to produce their papers, the results are a meaningless exercise in crunching numbers. These people need to spend less time on their laptops and more time in the real world.

I admit I’m biased. I live in a rent-controlled apartment, and if it wasn’t for LA’s Rent Stabilization Ordinance I would have had to move out a long time ago. But I still say that the economists who argue against rent control haven’t done the research necessary to support their arguments. If you’re still with me at this point, you might be saying, Okay, so what kind of research should we be doing?

I’m glad you asked.

First, a credible study on the impacts of rent control shouldn’t be focussed just on rent control. It should look at housing accessibility in both controlled and free markets. It should cover a range of major US cities. It should include data covering at least a 20 year period, and 30 or 40 years would be even better.

Second, it should look at various measures of accessibility. I think the level of rent burden is the best indicator for tenants, but it would probably also be good to look at homeowners and gather data on their level of mortgage debt. A thorough study would also examine data on evictions and foreclosures, but the first category could be tricky. In LA we have data on evictions under the Ellis Act, but Ellis is only invoked for rent-controlled units. If tenants leave because the rent rises sharply, or because the landlord offered them $3,000 to get out, or because the owner threatened to call ICE on a family of undocumented immigrants, there won’t be any record of their departure. And while most cities would have records of cases where tenants are evicted through a legal process, I bet those cases rarely reflect the real rate of displacement.

And third, how about actually going out into the world and talking to the people who are struggling to keep a roof over their head? How about making this an interdisciplinary study that ties housing accessibility to income, education, location, race and culture? How about looking at housing in the context of the real world, instead of looking at it as a set of numbers on a spreadsheet. The thing that makes me angriest about the papers these economists have produced is that they seem completely cut off from the world around them. When I read that the Bureau of Labor Statistics says the median annual wage for economists was $102,490 in May 2017, can you blame me if the words “ivory tower” come to mind?

I realize a study like the one I’m talking about would cost a lot of money and take years to produce. But it’s time for economists to get out of libraries and conference rooms and spend some time in the world the rest of us live in. The rising cost of keeping a roof over your head is dragging millions of people down across the country. We’re in the middle of a nationwide housing crisis. While the majority of economists feel comfortable slagging LA and New York for having rent control, they don’t seem to want to ask why the free market is failing renters in cities across the nation. If the free market is supposed to naturally produce affordable housing, then why are tenants in cities like Portland and Chicago pushing for legislation to limit rent increases?

Mr. Krugman, if you’ve read this far, I want to thank you for hearing me out. The reason I decided to direct this letter to you is that, of the economists I’m aware of, you seem to realize that economics isn’t just about graphs and algorithms. It’s about people. It’s about whether people can find a job, whether they can put food on the table, and whether they can keep a roof over their head. As you know, in spite of the fact that unemployment is nearing historic lows, there are millions of tenants across the US who are struggling to make rent. Over the last fifteen years, real estate investment has become a global force, with investors targeting cities around the planet looking for the highest possible rate of return. This has caused housing costs to soar in cities as diverse as Los Angeles, Chicago, Toronto, London, and Hong Kong. The argument that we can build our way out of this crisis doesn’t seem credible, since the vast majority of new units built in these cities are far too expensive for the average citizen.

It’s time for economists to stop asking whether or not rent control works. They need to start asking whether the housing market, regulated or not, is working for the millions of Americans who are living a paycheck away from the street. They need to step outside the university campuses and the think tanks and take a good hard look at how difficult it is for average citizens to keep a roof over their head these days. Economists need to look beyond individual cities. They need to start asking bigger questions. They need to make an effort to see human beings as something more than numbers on a spreadsheet.

Until these economists open their eyes wide enough to look at the big picture, their research won’t be worth the paper it’s printed on.