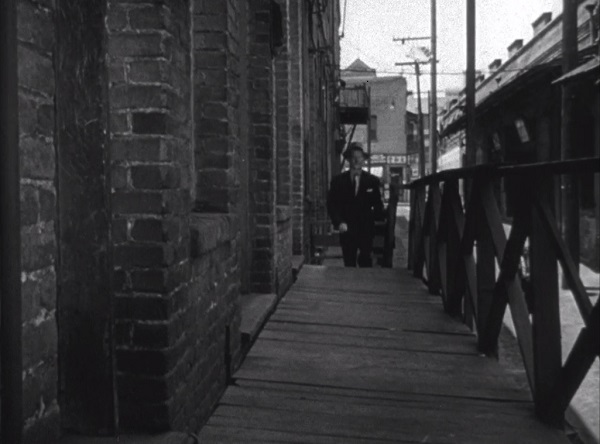

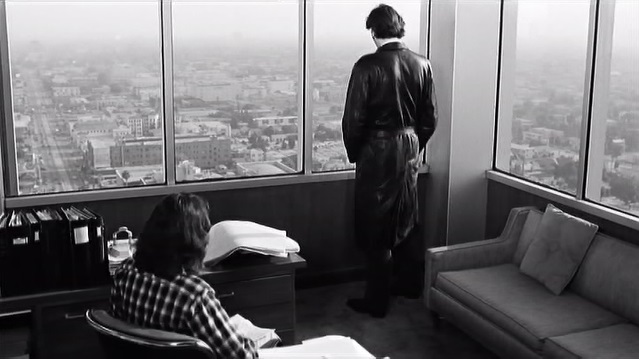

A view of Downtown circa 1960 from The Exiles.

Los Angeles has changed a lot over the past hundred years. Rapid population growth, rampant real estate speculation and a slew of technological advances have caused the city to expand and mutate with amazing speed. And one of the most interesting things about LA is that it has recorded those changes since almost the beginning of the 20th century. As the center of the global film industry, and a major hub for all media, it’s always in one spotlight or another. You might say Los Angeles is obsessed with seeing itself in the mirror.

When the film industry first moved west back in the teens, there were a number of production companies shooting silent two-reelers on LA’s streets. Nobody was thinking about documenting the city as it was beginning to grow. Location shooting was just a cheap way to make movies. Hollywood silents made before 1920 are filled with scenes of the city’s early days, but because there hadn’t been much development and few of the familiar landmarks existed, it’s often hard to identify the streets and neighborhoods that appear in the background.

In the 20s Hollywood became studio bound, and for about two decades location shooting was the exception rather than the norm. But in the 40s studio crews started to venture back out into the streets. Many of the crime films shot after WWII used LA as a backdrop for the action. In the 60s, independent filmmakers started shooting all kinds of movies on the city’s streets. By the 80s filmmakers had begun to use the city self-consciously, making deliberate references not just to the city’s past but to its movie past.

Looking at the films shot over the years on LA’s streets we can see a broad panorama of the city’s history, but one that’s still maddeningly incomplete. While some locations appear over and again, there are whole communities that never appear at all. And so much of it is totally random. In a few cases filmmakers deliberately set out to take a good, hard look at the landscape and the people. Others focussed on famous landmarks that have a specific meaning for movie audiences, or used their settings to evoke nostalgia. And others just didn’t have the money to shoot anywhere else and let their location scout call the shots.

I watch a lot of movies, and as I’ve gotten older, I’m more aware than ever of how they reflect the changes that have happened over the course of LA’s history. I’m especially fascinated by images of things that no longer exist. Change is inevitable. The city’s landscape is never the same from one day to the next. Even when the streets and structures stay the same, the people, the customs, the culture keep changing, and that transforms the landscape, too.

In this post I’m pulling together images of places and spaces that have disappeared. I’ve been thinking about doing something like this for a while. It took me months to get around to it. I spent a lot of time trying to figure out which movies to focus on, but I can’t even explain why I ended up choosing these six. The only thing they have in common is that they show pieces of LA that no longer exist. And trying to approach them in some kind of order was impossible. Or maybe better to say there were too many possibilities. Should I have organized them by the year the films were made? Or maybe used the locations to tell some kind of story? Or should I have tried to find a theme that ties them all together?

In the end I just decided to dive in and let my intuition guide me. This post may not even make sense, but hopefully you’ll get something out of the images. Let’s start in Downtown….

In the late 50s, Kent Mackenzie began working on a film set in Bunker Hill that focussed on the Native American community living in the area. The Exiles took over three years to make, and the production had more than its share of problems, but the end result was a unique blend of documentary and fiction that gave voice to people whose voices had never been heard before. Bunker Hill began in the 19th century as one of the city’s first upscale developments. By the middle of the 20th century the rich were long gone, and the aging homes that remained now housed a diverse low-income community. The Native Americans who lived there had left the reservations behind, looking for a different kind of life. In LA they were relegated to the margins of society, but living in Bunker Hill they at least had some kind of community. That lasted until City Hall declared the area “blighted”, and began pushing residents out as civic leaders and business interests pursued a massive redevelopment project.

Angel’s Flight climbing Bunker Hill next to the Third Street Tunnel.

A closer shot of Angel’s Flight with apartments in the background.

The Exiles captures the lives of three Native Americans as they live through a single night in Downtown LA. Shot entirely on location, it shows these people in their homes, on the streets, in bars and juke joints, and finally gathering on a hill that looks out over the nighttime landscape. It’s a vivid picture of a vanished world.

One of the vanished streets of Bunker Hill.

Displacement is a recurring theme that runs through the whole history of Los Angeles. The city’s original Chinatown was situated on the edge of Downtown, straddling Alameda between Aliso and Macy (now Cesar Chavez Avenue). But in the 20s voters approved funds for a new rail terminal, and much of the Chinese community had to relocate to make way for Union Station.

In the late 40s Anthony Mann made a startling series of thrillers, often giving them a sense of immediacy by shooting on real locations. Much of T-Men is shot in LA, and it features glimpses of what was left of Chinatown in 1947. Check out this first still, which shows a determined US Treasury agent walking across Alameda with Union Station in the background.

Dennis O’Keefe crossing Alameda Street in T-Men.

Then the camera pans to follow him, and on the west side of Alameda we see Ferguson Alley, a remnant of the original Chinese community.

Ferguson Alley, one of the last remnants of LA’s original Chinatown.

Our hero visits a number of herbalists looking for someone who recalls selling a specific blend to a certain man. It’s a brief montage, but it gives us a look at what was left of early Chinatown after WWII. Eventually, these buildings were also levelled. After some false starts, a new, more modern, and more touristy, Chinatown was built to the north and west of the original site.

O’Keefe mounts the stairs to an herbalist’s shop.

Crime Wave, directed by André de Toth, was also shot largely on location and gives a sweeping view of Los Angeles in the 50s. While it features a number of Downtown locales, the climactic bank heist takes place across the LA River in Glendale. The suburbs were thriving in the first decade after the war, and the film gives us a view of what Brand Boulevard looked like back in the day. In this scene we’re riding with Gene Nelson and Ted de Corsia as they drive up to the Bank of America at the corner of Brand and Broadway.

The Bank of America at Brand and Broadway in Glendale.

The suburbs were a product of car culture, and cars are central to the story. The main character is an ex-con who’s forced to become the gang’s getaway driver. The scenes before and after the robbery offer numerous shots from the perspective of the man behind the wheel. And an abandoned car serves as an important key in the cops’ search to track down the criminals.

The corner of Brand and Broadway.

Ted de Corsia inside the Bank of America.

Crime Wave is tough as nails and brimming with tension, but even if you’re not into classic crime flicks, it’s worth watching for the way it maps out the city in the 50s. The final car chase more or less follows the actual path you’d take from Glendale back to Downtown, speeding down Brand toward the Hyperion Bridge.

Another shot of Brand near Broadway.

By the late 60s suburbia had spread across the San Fernando Valley. Car culture played a major role in the rapid proliferation of housing tracts tied together by the ever expanding freeway system. Thousands of families moved to the suburbs in pursuit of a placid and prosperous lifestyle.

Which was an illusion. You can escape the city, but you can’t escape reality. The US was going through a violent upheaval, rocked by a string of political assassinations and a growing protest movement. Director Peter Bogdanovich looked past the supermarkets and the swimming pools and saw a side of the suburbs that most people were determined to ignore. Bogdanovich had been doing odd jobs for low-budget director/producer Roger Corman. Through Corman he got a chance to direct his first feature, Targets. The film follows a young man living with his parents and his wife in a tidy little house in the Valley, who one day picks up a gun and starts shooting people.

Targets is an innovative and unnerving look at the suburbs, America’s obsession with guns, and our twisted relationship with the movies. After following the young killer as he randomly picks off a number of unsuspecting victims, Bogdanovich stages a chilling climax that offers a complex reflection of the American landscape at the time. Cars lined up in rows at a drive-in movie, moms, dads, children and teens watching a horror flick unfold, when suddenly a sniper starts shooting at the audience from behind the screen.

The marquee at the Reseda Drive-In.

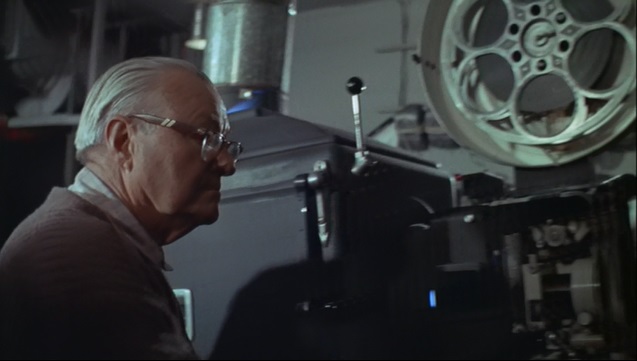

The film was shot at the Reseda Drive-In, which was located at the corner of Reseda and Vanowen. It survived into the 70s, when it was torn down and replaced by a business park. Aside from the fact that it’s an arresting and original debut feature (one of Bogdanovich’s best), Targets also offers a fascinating glimpse of the vanished world of drive-in theatres. Passionately devoted to movies since childhood, the director records every aspect of the experience, from the people visiting the snack bar to the projectionist putting the reels in motion.

The drive-in before the show starts.

The playground near the screen.

The snack bar.

The projectionist setting the film in motion.

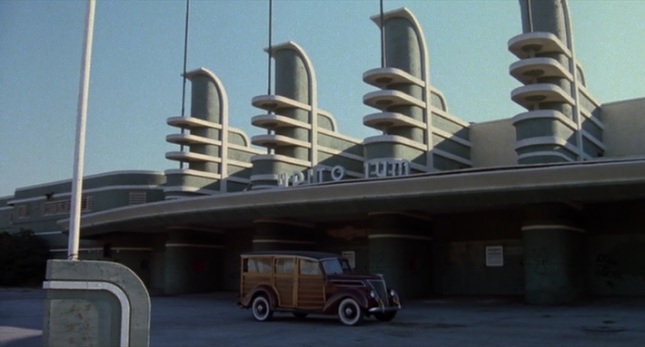

Hollywood has always been shameless about the strategies it uses to lure audiences to the movies. Two of the most common tactics are jumping on whatever fad is currently sweeping the nation, and exploiting people’s nostalgia for a past that never existed. Xanadu tries to do both at the same time. The story follows the efforts of two men, inspired by a muse, who come together to create a new nightclub that will bring back the glory of the big band era while catering to the roller disco crowd. Yeah, it’s a pretty strange movie, and one that will probably only appeal to those with a taste for bizarre kitsch. But I found out that parts of it were shot at the Pan-Pacific Auditorium, and decided I had to check it out.

The front of the Pan-Pacific Auditorium.

A closer shot of the Pan-Pacific.

For years the Pan-Pacific was a major venue, hosting car shows, sporting events and the Ice Capades. Designed by the firm of Wurdeman and Becket, the striking streamline moderne facade was one of LA’s architectural landmarks for decades. But it closed in the 70s, and though it was later listed on the National Register of Historic Places, no one was able to find a way to make it viable again. It was destroyed by fire in 1989.

Another view of the Pan-Pacific.

It’s possible that if the Pan-Pacific had survived a while longer, it might have been revived. The local preservation movement was just taking shape in the 80s. But for years Los Angeles was seen as a city without a history, in large part because the people who lived here didn’t have a sense of its history. Buildings were put up and knocked down based on whatever the market dictated, and few people worried about what was lost in the process. Visitors from other places talked about how the city felt impermanent, and complained about a sense of rootlessness.

Having lived here all my life, I don’t see it that way, and I’ve had a hard time understanding what people from other places are talking about. But I think I got a taste of it the last time I watched Wim Wender’s The State of Things. It tells the story of a director shooting a sci-fi film in Europe whose funding dries up, and he flies to LA to get some answers. Friedrich picks up a rental car at LAX and sets out to track his producer down, speeding along the the endless freeways, cruising the wide boulevards of Hollywood and Century City. He seems lost, totally disconnected from the city around him. Watching the film again recently I think I began to understand the sense of disclocation so many complain about. Friedrich is just one more in a long line of European filmmakers who have found themselves wandering LA’s vast landscapes, squinting into the sun as they try to make sense of it all.

Friedrich, played by Patrick Bauchau, cruising down the freeway in a rental car.

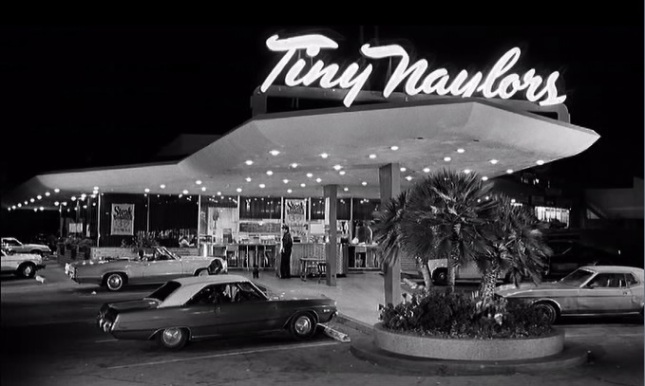

Many of LA’s buildings were never meant to be permanent. They were constructed by people who saw a market for a product and moved quickly to jump on whatever trend was popular at that moment. The roadside restaurants and coffee shops that started springing up after WWII weren’t meant to last forever. They were meant to catch a driver’s attention and pull them in before they sped past. The commercial architects who worked on these projects in the 50s quickly realized that the more extravagant and unusual a building was, the more likely it was to draw people in. The building became its own advertisement.

Tiny Naylor’s at the corner of Sunset and La Brea.

Bauchau orders a cup of coffee from a car hop.

As I said, nobody thought these structures would last through the ages. But as the years wore on, architects and critics began to value these brash, flashy buildings. And the people who had frequented these places had gotten attached to them. In the 60s if a developer had levelled one of these coffee shops, nobody would have batted an eye. By the 90s, preservationists were arguing that they held a special place in the area’s culture and should be protected.

Another shot of Tiny Naylor’s.

That was too late for Tiny Naylor’s, located at Sunset and La Brea. The building, a Googie masterpiece by architect Douglas Honnold, was designed so that people could park outside and be served in their cars, a common feature of coffee shops from the era. The State of Things, released in 1982, captures Tiny Naylor’s in all its glory. A few years later it was torn down and replaced with a shopping mall.

The argument over what should be saved and what should be torn down will go on for as long as LA exists, and that’s part of the dynamic of any urban area. Cities are formed by the tension between the past and the future. LA will go on changing. And the movies will go on watching it change.

Bauchau in an office building at Sunset and Vine, gazing at the LA landscape as it stretches out to the horizon.